Boston

My reasons for the trip were a bit of a mystery even to myself. For a couple of months I had offered various thoughts to friends, none of which felt particularly accurate. Part certainly came from being without a bed to call my own, having let my lease go at the end of August. I had the ambition of playing professional golf, and fall was to be my time to try to qualify for the tour. After miserable results during my summer tournaments though, it was utterly clear that I was not ready. Such an attempt costs an entry fee of around $5,000, so nothing to take lightly if you are not feeling confident. Thus I found myself in September no longer living with my best pals from college, and without much of an idea for what came next.

This was only a fraction of the reason though. A new lease is not hard to find in Boston, and the ties to a great group of college friends and my girlfriend were strong incentives to stay. Instead, the call to the road came mostly from desire rather than necessity. A New York City kid, schooled and living in Boston, I was decidedly unacquainted with much of the country. From a youth spent playing golf and soccer tournaments, I knew the eastern seaboard from Maine to North Carolina, but had only jetted in and out of a handful of other places around the country. This fed a sense of claustrophobia and restlessness.

Growing up in a family where my father often referenced his great journeys across the country and around the globe, and in a country where individualism and exploration are part of its ethos, such a trip felt like a requirement of a well-lived life. Soon to be 25, I saw many a long path before me. Qualifying and playing golf into my 30s. Starting a company with its many early years of hard toil. A serious relationship and eventually the demands of a family. All roads leading away from free time and the long one. Maybe premature, but fleeting opportunities on the horizon and the sinking feeling of passing youth were strong factors in deciding to leave and traverse the states.

This is not an exhaustive list of my reasons. Many more I have yet to suss out are lurking in the recesses of my mind. I haven't tried too hard to figure them out though. The important thing was that I was going.

And so I found myself sitting in front of my boss, in a newly renovated yet still sparsely decorated office, asking what he thought about me working remotely.

“My sister is in Houston. She is a reporter there. Growing up in New York, I have lived in Boston for six years now, with school and now Redline, and I am growing kind of tired of it.”

“Six years, I’ve lived here for 43 years,” Mark interjected.

“Hahaha, yeah I don't know, I just want a change out of the northeast...and I was thinking about joining her in Texas. What do you think about me moving to remote work?”

This was more than an arm’s length from the truth, but I did not want to make it too complicated for him. I planned to depart in early October, with stops in Buffalo, Cedar Rapids, Rapid City, Denver, Jackson Hole, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Austin, Houston, and New Orleans by Christmas. For the past couple of years, rather than exchanging presents, my family took a trip. This year we were heading to New Orleans, which made it the logical time and place for the trip to end. Once January hit I planned on coming back east for a few weeks to visit my girlfriend and former housemates. Then heading back to Texas, possibly Houston, for February, March, and April, to prepare for the upcoming golf season. Houston was definitely a stop on the trip and possibly my location in the spring, but I told my boss Houston because working remotely from Texas sounded a lot better than working from the road on a 10,000-mile 3-month-long road trip. From my perspective, remote work was remote work, and as long as I was completing my assignments, it did not matter where I was located. I just needed my boss to say yes. I also thought there was little possibility that work would find out about the plan.

For a pretty low key guy who gives his employees a long leash, Mark took a long while to consider this idea. For two weeks, I came into work thinking I’d hear his decision. I’d see Mark walk into my office and think he’d say “Owen, do you have a moment?” and sweep his hand in the direction of his office; instead he would ask how progress was going on one customer ticket or another. Due to my initial procrastination in asking and Mark taking longer than expected in answering, it was late August at this point and my lease was up in 11 days. I needed to know where I stood, so if I did not get approval, I could act quickly to find a lease starting in September.

I walked into his office in the late afternoon, after Mark was finished with his multiple morning calls, and after I had time to complete enough work so I could give a positive status update if I was asked. Knocking on the door, “Hey Mark, do you have a moment?” Assent given with a nod of the head. “Have you had a chance to review my request? My lease is coming up and I kinda need to know one way or the other.” “Yes, yes, Houston, that's okay. Performance must stay high. Working remotely there are fewer remedies if performance drops.” “Thank you very much, Mark!! I do not see any reason why performance would drop.” The two senior engineers on my team also worked remotely so all questions I had during a day of work had to be asked across the company chat app, Slack, anyway. My excitement made me pop up out of my chair and shake his hand. I was going, going on the long one.

It had been over a month since I had been approved to work remotely, and I had spent my time bumming around Boston. September is a glorious month in the bay state, so I hung around, staying at Isabel’s and on friends' couches. Wonderful activities ensued; a weekend on the cape with my housemates, a weekend in Newport with Isabel, a wedding of a family friend in the Berkshires. It was a charmed month. Not having a place to stay made my departure feel imminent and thus activities and emotions were at heightened levels.

It was a month of extra rounds and toasts; toasts to the end of the college lifestyle and the past two years together. Friends from college, we had made the conscious decision that we wanted to live together after graduation. We thought at no other time of life were we going to be able to live with 3 of our best friends. Although we had various ideal paths for ourselves we thought living together would be an experience we would rue missing. It was more than we could have hoped for. Trying to explain such friendships always comes up short and sounds all too clique, but we really were guys who cared about one another. Thus this month was more than me leaving; a couple of our other friends had left a few months before and one of my housemates Zach was thinking of moving to DC come January, so the post-grad era was ending. Our friendships were likely at their most intense. We did not want it to, but life was moving us on.

Finally, I had all my stuff packed and on the curb next to my car at 9:15 on Thursday morning. Isabel had taken two days off work, the first to head north to visit her mother for her 60th birthday, and the second for us to drive out to Buffalo. I planned on staying at the housemates Thursday night and picking Iz up wherever her sister dropped her off Friday morning. Thus my box of snacks, my two bags of clothes, my suit bag, my golf bag, my camping gear, my kettlebell, my toolbox, and an extra pillow were all strewn on the wetness beside Norman. With Norman, a little two-door Hyundai Accent Hatchback, packing had to be deliberate. Golf bag on the left side, clothes bags on the top of the folded down back seats, snacks and camping gear on the flat nearest the trunk door, and finally pillow and kettlebell wedged behind the passenger seat.

“Big road trip?”

“Indeed, I am driving cross country to San Francisco.”

“Oh my. I did that once. Nebraska was sooo goddamn boring. Flat and endless. What route are you taking?”

“I-90! At least most of the way. Buffalo, Iowa, the Dakotas, Denver, Jackson Hole, San Fran!”

“A lotta driving. Best of luck. Have fun!”

My phone said 9:41, I was quite late for work. I’d need 29 minutes of speeding to make my morning meeting at 10:10. I jumped in the car and sped off, leaving my suit bag right there, on the 3ft tall rock ballast which marked the start of the stairs up to the yellow house, the first one on the right of Lee st.

At work, I was in serious shit. I’d gotten a bit confused about if Isabel and I were taking Friday off to drive to Buffalo early or if we were leaving after work on Friday. She had lived in Buffalo the year before and had been asking me to go for a while. This trip provided the perfect opportunity. Buffalo was on the direct route out, seven hours west on I-90 from Boston. We’d discussed driving after work on Friday but it meant the weekend activities would be very cramped. On the other hand, leaving early Friday would require taking a day off, a commodity that Isabel was running low on. Confused about our decision, I did not realize my error until after I had put in my request to take the following week off. I am not proud of it, but I felt weird about asking for another vacation day given how nice they had been in granting me remote work, and so I kept procrastinating. I finally came up with the plan that I would ask for the day off because the packing was going very badly. In their minds, I was packing up and would be taking the following week off to drive down to Texas, where I would set up shop for the foreseeable future. I would say packing was going so poorly that I thought I’d need to take Friday off in order to finish.

But now I was late! It was 9:41 and I needed to ask this morning! I surely couldn't show up late to our already very leisurely 10:10 meeting and ask for the following day off! I sped. Through Cambridge, onto route 28, and up 1-93 to Woburn. I sprinted up the stairs, put my stuff down, composed myself, wiped the perspiration on my forehead, and walked into Mark’s office for our morning meeting. The plan was to ask at the end of the meeting when Mark would ask “Anybody have anything else?” With the wording and tone of my request running through my head on repeat, Mark mentioned that he would be out the next day and thus no meeting. I started to think, to conspire. Not proud, not proud, very very guilty. In my dread I kept my mouth shut leaving the insidious plot of just not working on Friday. Without the morning meeting, nobody would check in on me, certainly not on a Friday. None of my work was time-critical and I would be able to make it up in the week I had actually taken off. And so I found myself picking up Isabel at 10:30 on a day when I was on the clock. Iz had made such a big deal about how hard it had been for her to take the day off that I had absolutely no courage to tell her about my mischievousness.

The timing for Iz could not have been worse work-wise. Having been put on three upcoming deals, she had worked 12 hour days Monday-Wednesday, only to have to work in the car on the drive out. Huddled over her computer on her vacation day, her focus was so intense that she could not hear the outside world. My questions were not heard much less responded to. After four hours of that, plus not being able to listen to any of my downloaded books because Iz also wanted to listen to them, I was drowsy, testy, and was not having fun. I needed a short snooze and Iz had a call so we switched seats and Iz would talk as she drove.

Waking up quite dazed and groggy, I looked down to see the car keys in my lap, my phone 56 minutes advanced, and the car parked in a service area. Confused, I shuffled out of the car to go to the bathroom and find Iz. Not finding her inside the building or outside on the benches I was befuddled. I went back to the car to get my water bottle, locked the car with the driver’s side door button because the key fob seemed to have died, and returned to the building for a second search. I found her near an outlet, hidden by a massage chair, huddled over her computer, typing furiously. She had made it 35 minutes before pulling off and getting back online.

Still drowsy but exasperated by our slow pace I said I would drive. Getting back in the car I pulled onto the highway and noticed there was definitely something wrong. There was a red light on the dashboard with the letters “tpms”, the clock was blank, the trip odometer had reset to 0, and the interior lights weren’t working either. Thinking back to the service area I wondered if these were related to the car keys not being able to lock or unlock the car remotely. Asking Iz if anything had happened while she was driving, I got no response. Not knowing what was wrong with my car, but knowing something was definitely up, on the opening leg of a 5,000-mile journey, in the presence of a mute companion, my voice cranked up to a volume and tone much too dramatic.

Having decided to start dating a year before we were both immensely pleased with how it was going. And I do mean decided. With our fathers being best friends from college and our families still close, we had discussions before making the plunge, not wanting to get wet if the relationship didn't have legs. Six months after giving it a shot we had looped the parents in on the situation, much to their audible chagrin. “Don't screw this up for us.” Regardless, no damage was done. A year in and we were enjoying each other's company immensely. All of this to say, we wanted to have a good weekend. I wasn't sure where life would take me after this road trip, but I did not think a return to Boston was in the cards. Six years of living there, long winters, and a world of wonders, weighed against it. This might be our last weekend before a long-term long-distance relationship.

Isabel’s dismissive responses to my continued questions about if something had happened to the car, did nothing to dilute my tone or rising worry. Pulling over to the side of I-90 somewhere between Albany and Rochester on a sunny, blustery, fall day, the first car investigation of the trip ensued. The hood was raised, the manual brought out, and phones sent into action. Much to our novice delight, 10 minutes later we had the working theory that it was a blown fuse, one that controlled the interior lights, clock, odometer, and a couple of other things. The details in the manual and our observations matched up. Unable to get the broken fuse out of the power connector box, an item whose existence we had just learned of, we hopped back in the car and proceeded on our way, our worry eased that anything serious was actually wrong.

Not yet well acquainted with the practice of arguing we laughed about how we had gotten a bit taken away.

Darkness descended right around the time when we were arriving at Niagara Falls. Isabel forgot to bring her passport so we were relegated to the US side. All the pictures which pop into your mind when you think of the falls are from the Canadian side. The US side looks down from the top of the falls, whereas the Canadians have the full expanse of the falls, which makes for some great pictures.

We found the US side absolutely exhilarating though. Isabel had been to the falls a few times but always from the Canadian side, and found the view down the falls, especially from Luna Island, heart pounding. The water crested over the edge and dashed down 150 feet onto massive boulders which had broken off the falls years before. Across the way, there were massive flood lights with rotating colors focused on the falls for the evening onlookers delight. The light interacting with the mist, just barely illuminating the drenched boulders below, was mesmerizing. Iz and I went back and forth trying to explain the scene. “It's apocalyptic!” “Looks like the coastline of Maine when a big storm is bearing down.” “These rocks are what specs of dirt would be in a human shower.” From stop to stop within Niagara State Park we would run, just too excited to be there and pumped up from the otherworldly scene below.

From Niagara we headed to the consensus best buffalo wings in Buffalo and a quick tour around Isabel’s old neighborhood, Gabriel’s Gate. It is an old-timey restaurant in a two story house, with wood paneling, wooden bench seating, and huge animal busts peering down at out from above the bar. The food ain’t fancy, just two dozen gloriously lathered wings with wooden discard bowls. Surrounding it is the neighborhood of Allentown, which contains a combination of stately 1800’s mansions, leftover from the golden age of the Erie Canal, interspersed among vacant lots and spots of gentrification. Isabel pointed out some of her favorite haunts and told stories of this or that when somethings around us reminded her. A bit after 10pm we headed to the Airbnb.

“Bad, bad, not good.”

“What?”

“My jacket bag.”

“You left it?”

“Bad.” Shaking my head.

“You left it at my apartment?”

“Worse.”

“You left it with the roommates at 91?”

“Worse.”

“You left it at J and Travis’s?”

“Worse.” Bumping my head against the side of the car now.

“You left it on the street?”

“Indeed.”

“NOOOOOOO!”, Isabel let out sympathetically. “That's literally the worst-case scenario. My house or 91 and I coulda just sent it. What are you gonna do? The Dakotas and Jackson are gonna be cooold.”

There followed a sizable pause to let the news sink into both of us. All of my jackets and warm weather clothes were MIA, left on the stoop of a random house on Lee St. in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A cool fall evening bringing the bag’s absence to my eye when I opened the trunk. Remaining was the sweatshirt on my back and about 10 t-shirts.

Friends from Isabel’s old job joined by significant others and siblings had all rented a house in Ellicottville, a little way out of Buffalo, as our home base for Fall Fest, the biggest harvest festival in Western New York, and invited us to join for the weekend. The result was 16 people in an Airbnb with beds for 9 and two couches. Isabel and I were assigned to the top bunk of a twin bed bunk bed. It was to be a cozy final weekend together.

Fall fest turned out to consist of a few stages for live music, 100 or so street fair vendors, an assortment of fried foods, and tons of people, all situated in a very picturesque town a bit outside of Buffalo. Two-story brick buildings with cute shops, the classic white steeple church, beautiful fall foliage, and lovely fall weather. Isabel’s friends were super nice, and we spent our days eating and drinking our way through town.

The Dakotas

At 11:45pm I awoke from my slumber. Having pulled over at 8:30pm to take a one-hour nap, I somehow had slept for three hours and fifteen minutes. Just a bit outside Cleveland now, I had 8.5 more hours of driving to do before Noah’s flight landed in Iowa at 1 pm the next day. Having left Isabel in Buffalo around 4 pm, I’d cruised through a stunning section of Western New York, where leaves of yellow and red dotted the hills far on my left, vineyard after vineyard ticked by on both sides of me, and the sparkling blue of the Erie could be seen off in the distance on my right. The fading sun threw a golden light over the whole scene making it one of the prettiest sections of the entire trip.

After making good time to Cleveland I took a pit stop in Cleveland Heights to take a look at my father's childhood home. He had lived there in his elementary school years and had been encouraging me to make the stop. It was a stately brick home on the corner, with a chatty couple sipping wine on the back patio. Other homes in the neighborhood were also very nice, many in the Tudor style, with full green lawns and a nicely sized backyard. Yet looking up prices online at dinner the houses in the neighborhood were mostly in the 200-300k range!

I got a bit tired an hour later, four hours into the drive, and still 3.5 hours from my planned pit stop in South Bend, Indiana. That is when I decided to pull over into the service area to take a nap. Awake now and flustered by my unplanned hibernation, I got out of the car to take a piss, only to slip on some vomit spewed directly outside the driver’s side door. Tough go, but at least I was fully recharged. I reevaluated, decided not to pee, and took off down the highway, lots of driving ahead of me.

Usually, I like driving at night. For one there is much less traffic, but mostly I like that it means I am not wasting a day in the car. On my many trips back and forth from NY and Boston, I would usually leave around 9 pm, after dinner with the parents or a night hanging with the housemates, and complete the drive in 3:15 hours. It felt like I got two full days on either side of the drive. On the drive to South Bend though, I had the sinking feeling that I was missing out. The whole point of this trip was to see the in-between. To experience all the places that I had never been to before. But under the cover of darkness, the landscape's charms were hidden. Every road looks the same at night: black asphalt, painted lines, darkness above and on each side. And so Indiana passed by, a mystery to me. I decided in these wee hours to try and favor daytime drives so that I would not miss the in-betweens.

A quick 5-hour stopover at a Motel 8 and I was back on the road. It was 8:01am and google maps predicted 4 hours and 58 minutes, just enough to beat Noah’s plane in Cedar Rapids at 1 pm. Looking around, I realized I probably had not missed much in Indiana if it looked at all like Illinois. I-90 cuts through the outskirts of Chicago’s sprawl and for a couple of hours it was nothing but wide concrete highways, billboards, spaghetti ramps, and hints of strip malls off to the sides. It was monotonous and depressing, such that the cornfields of Iowa were actually a joyous sight.

Small farms of corn and soybean, Iowa was exactly as I had imagined. No place on the trip fit with its stereotype quite as well as Iowa. I mean that in a positive way. It looked like the Jeffersonian ideal. The farmhouses and silos were the only interruptions to the lines of agriculture flitting by row after row. It was mesmerizing watching out of the corner of my eye, each perfectly planted row going tick tick tick. Even the soybeans and grass fields had these perfectly sowed lines. An entire field of grass looked like matted hair from almost every angle until for a few brief moments the field came into perfect organization with crop lines going off into the distance.

Arriving at the Cedar Rapids Airport was a funny experience being accustomed to the hustle and bustle of LaGuardia or JFK. Not a single car or person was in front of the single terminal airport. The sidewalk in front stretched for 500 ft and not a single soul was present. I leisurely parked right in front and hopped out, not worrying about a screaming traffic cop or honking taxis. Noah walked out a couple of minutes later and we took off, no sign of his fellow passengers or any airport personnel materialized.

We didn't have any definitive plans for the week. We knew we wanted to go to Badlands National Park, Theodore Roosevelt National Park (Noah very much wanted to say he had been to North Dakota), and Mt. Rushmore in the Black Hills. The dates of when to do these things or the stuff we’d do in between were unsettled. It was novel for both of us to spend a vacation like this. Usually, vacations were well-planned out affairs so as to maximize the activities that were possible. Or even on vacations whose purpose was relaxation, there was still a known place and routine to the day. Here we had the true road trip experience: young, excited, and untethered.

While driving we decided on the Castle Trail at Badlands National Park for Wednesday so we’d spend the rest of Monday and Tuesday tootling around Iowa and South Dakota. 9 holes of golf near Des Moines, a failed attempt at attending a 2020 presidential campaign event, a sightseeing stop at the Corn Palace in Mitchell SD, an active native American archeological site nearby, and a pit stop in Chamberlain South Dakota to try to fix Norman.

The fuse had still not been fixed, the driver side visor had a tendency to dislodge and fall down 10 inches into the face of the driver whenever we hit a big bump, and the hood's screws had become loose causing the whole hood to shake vigorously at high speeds. Chamberlain was a small town on the banks of the Missouri River consisting of 20 or so businesses. Stop one, right in the center of town, the mechanic said he was sorry but he had a backlog of work that would take him into the following week. 2pm on a Tuesday in an all but forgotten town in South Dakota and the mechanic had a week worth of cars waiting?!? The mechanic was nice enough to recommend a place down the street but warned that the old man there hated foreign cars and might refuse to work on my Hyundai. Rather excited to meet such a character we were disappointed and perplexed when we found his store closed for the day, at 2:15 on a Tuesday. Thwarted, we were headed out of town when Noah spotted a NAPA Autoparts store and thought maybe they’d lend us the tools to do the fixes ourselves. MVP of the Dakotas, John of Napa Auto Parts, showed us how to take the fuse out of the power connector box, sold us some gorilla glue for the visor, and lent us some wrenches needed for tightening the screws of the hood. It was a very satisfying feeling to do all of these small fixes, all for the mighty sum of $4.10. I felt slightly capable, almost handy. This plus changing the oil and oil filter myself before the trip had me feeling like I was starting to get a grasp of how cars worked, something I had always wished I knew.

“Sssssss”

“AHHHHHH. HOLY SHIIIIT, HOLY SHIT, HOLY SHIT. “

“WAS THAT A RATTLESNAKE?” Noah asked after we had darted 20 yards back up the trail.

“YEAH. It was fucking two feet away. I looked down and it was a foot in front of me and a foot off the trail.”

We had seen signs warning of rattlesnakes when we had penned our names into the Castle Trail log, but holy shit! this one was right there. 4.1 miles down the trail. Now, with badlands on our left and grasslands to our right, we were a bit stuck. For much of the hike, the grasslands were relatively sparse and easy to traverse. Here, though, it was thick with brambles, plus we weren't sure if there were other snakes hidden nearby. The badlands, made from a very crumbly clay-like rock were poor for hiking. Footholds and handholds were likely to crumble beneath one's weight. Thus with a steep 15-foot slide marking the start of the badlands just a couple of feet off the trail on our left, looping around the snake on either side seemed untenable. We tried throwing rocks next to it, stomping and yelling, and shooing it with Noah’s portable tripod, all to no avail. All we managed to accomplish was to make it coil up and hiss even louder. Not knowing how dangerous rattlesnakes are, but knowing they are venomous of some kind, we decided we didn't need to see the last mile of the trail and decided to turn around.

Still only 10:27 AM, we’d already had an eventful day. We had woken up at 5:45am to witness the sunrise, the golden rays illuminating the striated rocks layers which gave the badlands their character. One million years before all we would have seen was a gentle river flowing through grassland. 500,000 years from now, the erosion would be so complete that the jagged ridgelines and beautifully colored striations showing the rock layers would be gone, returning the land to gently rolling grassland. We had arrived at the perfect time to see the area at its most spectacular. The highest ridgelines 700ft and the badlands extending for a 30-mile stretch, we could compare the relative ages of rock layers from two very separate sections all while the sun peeked over the horizon.

The only damper of the morning had been Noah’s new phone. An iPhone 11 with three cameras on the back, a wide lens, portrait mode, and night mode included. I quickly realized that my iPhone 5 SE’s photos were impotent. There was no point in me taking a picture if Noah was right there beside me taking the exact same shot. His photos would look so much better that I gave up trying, leaving my phone in my bag. For sunrise, I was his assistant recommending new viewpoints and angles that I thought might be good. On the trail, I wandered off into the outlying canyons of the badlands skidding and scurrying around as Noah paused and took professional quality pictures. What finally stopped all the picture taking was that snake. It scared the bejeezus out of us.

Noah took the lead on our way back, conversation all but ceased, our eyes focused downward on the lookout for other slithering reptiles. I was definitely skittish, taking offense at every sound, but Noah tried to say he wasn't. However, he hilariously timed “I’m not scared.” with the takeoff of a couple of birds in the grass; their wingbeats against the grass simulated the rattle of a rattlesnake shockingly well. Noah gave a yelp of fright and came running back up the trail like a scared Scooby Doo into the arms of Shaggy.

Stopping by the visitor center on our way out we bombarded the rangers with questions accumulated on the trail.

“Why are there some black sedimentary rocks interspersed in the runoff areas? They look very different than the crumbly rock of the badlands.”

“You’re exactly right, they were brought down from the Black Hills all the way here by the river that eroded the badlands.”

“How common are rattlesnake attacks?”

“We have 5 or 6 every year.”

“Are they deadly?”

“ Not usually for full-grown adults. If you get treatment within the first 30 minutes you are usually okay. Longer than that and there can be some clotting of the blood caused by the venom, which can be dangerous.”

“Are there any large animals in the park? We kept looking out and all the way to the horizon we couldn’t see a single one.”

“Yeah, there are more in the western section of the park. We have a herd of 3,000 buffalo. Or rather bison. Some bighorn sheep, prairie dogs, and black-footed ferrets are also over there.”

Like magic, as we headed out of the park through the western entrance, a cluster of bighorn sheep crossed the road right in front of us. 250lbs, with massive horns curved back behind them in a semi-circle, the sheep clomped their way across the pavement, paying absolutely no heed to the cars piling up. It was surreal being so close and made for a spectacular photo opportunity. Three male bighorn sheep grazed on the grass only a foot off the road, badlands rising 300 feet directly behind them, clear blue sky up above that. We gawked, Noah took photos, and I repeated “Oh Wow, SO COOL!” way too many times.

Not five minutes down the road, we rounded a curve to see mammoth dark spots dotting an expanse of grassland. We pulled over onto a little dirt road to watch. The bison having shed their winter fir, had a thick mane of curly black hair covering their front half while their backsides were covered in a much thinner coat similar to that of a cow. Most were far off in the distance, heads down in the grass, chomping very audibly. Yet there was one right near the road and he WAS COMING CLOSER. At 2,000 pounds he weighed far more than my little Hyundai Accent. We froze and the beast walked mere feet in front of us to go scratch on a stop sign. Back and forth it lurched, trying to itch its shoulder, the poor stop sign getting yanked to and fro, 15 degrees forward, then 15 degrees backward.

Stoked with our luck, bighorn sheep and bison RIGHT ON THE ROAD! when we hadn’t seen a single other wild mammal all day, even from a distance, we happily started on our way up to North Dakota.

I’m not sure how to feel about the scenic drives that almost every National Park has. Often a loop, they are designed to give the automotive visitor a quick hits album of what the park has to offer. I wanted to hate them, black stains that have no place in the most pristine lands our country has left. Yet I used them. They allowed me to see in a day what it would take a week of backpacking to see otherwise.

Theodore Roosevelt National Park had one of the nicer scenic drives. A 35-mile loop, closed in one section because the badlands underneath had eroded causing the road to collapse, had five scenic stopping points.

Stop one, the prairie dog settlements. These badlands of North Dakota were much farther along in the erosion process. The ranger in the visitor center said they were the friendlier version of Badlands National Park, their curves more rounded and vegetation far more plentiful. All of which made TR NP the perfect habitat for prairie dogs. About one foot tall, looking like oversized hamsters, they were everywhere. The crumbly rock made it easy for them to bury their homes and the vegetation made for a plentiful diet.

I rushed at them, sprinting hard for 15 yards directly at them. It felt a bit wrong, against the ethos of the National Parks, but a plaque detailing their different calls had made me too curious. A repeating yap when they spot danger, a jump and yip when the danger disappears, and many variations in between. “Prairie dogs have the most sophisticated vocal language ever decoded.” With most of their natural predators dead long ago we spent 10 minutes just watching them scurry about cropping the grass around their homes to one inch tall. We weren’t going to see any of their language if we didn't do something. My mad dash was in the name of science! One popped up, stood erect and gave a yelp, terrified of this rushing 165 pound man. All its neighbors heard the signal and scurried to their holes. This is how they survive. They keep their lawns short so predators can't sneak up, and they live in settlements by the thousands so someone is always on the lookout. The yelps kept coming, every two seconds. Then once I backed up, back onto the road, the vocal prairie dog jumped up, kicked its hind legs and yipped that all was safe again. Lawn mowing and neighborhood gossip resumed.

Stop two, Buck Hill, a knob from which two rangers with binoculars were pointing out wildlife in the distance. A pair of feral horses over there. A group of Elk so far in the distance they were barely even specs. All around us rounded buttes with painted rock layers poking out between the grassy tops and wooded ravines. The Lakota people were the first to call this place "mako sica" or "land bad." French-Canadian fur trappers called it "les mauvais terres pour traverse," or "bad lands to travel through." It’s crumbly and very uneven terrain with few water supplies made the land terrible for farming and treacherous to cross. Thus to the natives and early white settlers this was undesirable land, especially in comparison to the flat grasslands we had driven through for four hours on our way here. As a result, this was some of the only virgin grassland in the country. The second-most biodiverse ecosystem in the world, behind only the rainforest, the US has only 32% of its virgin grassland left. The rest has at some point or another been plowed under, with agriculture, roads, and buildings the main culprits. Looking straight down as we hiked the short nearby trail, I thought I could see the increased biodiversity. Maybe it’s because I was looking for it, but each patch of ground I looked at was remarkably rich. Saltgrass, western wheatgrass, creeping juniper creeping in patches, sagebrush making cameos, very young pine saplings poking up, and some lichen looking stuff was near the ground and in-between everything.

Stop three, an exposed old coal vein. Coal inside the earth can catch fire and when it does it creates a kiln like environment that bakes the clayey soil of the badlands. The result was bright red patches of ground where arrowhead sized shards of pottery covered the surface. We did the loop and were quite impressed with the scope of the area. The red was so vibrant and it was wild imagining the earth smoldering below us. That said, we left feeling like we must have made a wrong turn, we only saw a few small patches, no big vein as was described on the trailhead.

Stop four, the eroded section of the scenic road. Along a curve around the side of a butte, the ground beneath had just given way, taking the pavement with it. The road now fifteen feet below, left a large drainage pipe sticking out from the side of the butte. The ranger inside said the fix would cost $1 million, not something in budget for a Park Service three billion dollars short on maintenance work. It was remarkable to see, and yet more remarkable that it didn’t happen more often. After all, erosion is what happens in the badlands. It is the only constant. To build a road across such land seems like a Sisyphean task. No matter what was done, the ground beneath the road would eventually wash away. It was not a question of if, but how often.

Stop five: We raced back to a point near the start of the loop where the Little Missouri made a horseshoe curve through a section of badlands. It was the best place to watch the sunset and we were losing light quickly. Around curve after curve, we drummed up excitement for how great the scene would be. The light was perfect, as Noah would say “dynamic light”. We raced past beautiful pictures, thinking better was up ahead. We parked, raced up the slope, and oh my what a setting. On the left and right, the striations of the badlands sloped up at a 60-degree angle, looking like stadium seating for the Little Mousori flowing below. Beneath us and curving to our right for a bit was a 150ft foot cliff that the river had carved; colored white down near the shoreline and a thick stripe of yellow near the top. In the middle of the horseshoe, a 1000ft by 1000ft expanse of grass with yellow and green shrubs interspersed. They say when settlers first came upon this scene the entire central area was black with bison. “Squeezed in shoulder to shoulder there looked to be no more room, and yet still they were streaming in by the thousands down the slope.” Back then there were 3 million bison in the United States. By the time Theodore Roosevelt was president the beasts numbered in the hundreds. Through the conservation efforts of TR and many others, they number 250,000 today; 25,000 on public lands and 225,000 in private herds. In our time in the park, we saw maybe 75 of the estimated 25,000 on public lands.

As beautiful as the scene was, the sun had just dipped behind a bank of clouds on the horizon as we arrived ruining the National Geographic moment. At the highest viewpoint along the cliff, we met up with 10 or so other disappointed photographers. Set up with their $1,000+ cameras on tripods they were just standing around chatting, their fingers quivering from how many photos they’d taken in the previous hour. Now though, they waited, hoping the clouds would part and the sun would peak through for a final shot. We joined the gaggle and immediately they made us the center of attention. They were very happy to have two interested and unknowledgeable subjects, so we got a free 30-minute lesson on photography; the different telephoto lenses, how to frame the shot into thirds, how to not overexpose a scene, how some of the best shots happen after the sun goes down and the pink hues arrive so we should stick around, and on and on. They were all 50+. This was how they enjoyed the parks. Not up for hiking or backpacking, photography was their outlet. One man had lived 56 of his 60 years in ND and was spending his retirement driving around and photographing the national parks. “If I never go east of the Mississippi again I’ll be okay. All the good stuff is out here west of it.”

Driving out of Theodore Roosevelt, Noah and I discussed which park we had liked more. “I understand why TR came here to heal, it was so pastoral. It felt like such a friendly place to be,” Noah remarked. “Yeah so peaceful, imagine riding a horse over all those hills, Bison and Elk all over the place.” Theodore Roosevelt had come out here to Medora, ND to heal after his mother and wife died on the same day back in New York when he was 25. He became a cattle ranger and an assistant sheriff. He hunted, he healed, and he gained a new perspective on life. “If I had never gone out to ND, I would never have become President.” “Badlands NP was obviously stunning and better for photos, but it was such a harsh environment. I liked TR much more. It was just inherently pleasant on the eye. I could have sat there at Wind Canyon and just looked out for hours,” Noah said. “Yeah, Badlands was more spectacular, but I really want to come back here and spend the week, camping out and hiking around. Whereas I don't feel the need to go back to Badlands,” I responded.

I dropped Noah off at the Rapid City airport midday on Saturday after a quick morning nine. We’d spent the previous day craning our necks to see Mt. Rushmore and doing a very picturesque hike in Custer State Park. It had been a fantastic week. We’d both been accommodating of each other's desired itineraries, had many political and historical debates, and had gotten incredibly fortunate with the wildlife we’d seen. No lions, tigers, or bears, but bighorn sheep, bison, feral horses, rattlesnakes, elk, deer, prairie dogs, squirrels, chipmunks, and birds, birds, birds, oh my!

That said, I was somewhat glad to be back by myself. I was looking forward to putting on my audiobook and driving alone across a lonely landscape.

Highways and Byways

Roads were the lifeblood of my trip. I was on an interstate or U.S. highway almost entirely on my way from place to place. Most of that time consisted of setting cruise control to 80 mph and doing my best to not fall asleep as I sped across some supersized state. This was expected when I departed Boston. Distances needed to be traversed in tight time frames, so lollygagging on backroads was out of the question. What I did not expect was how much the history of our highways fascinated me, or how well their story explained the reasons for much of what I was seeing around me. So much so that when I felt the desire to put my trip on paper, I also felt like the story could not properly be told without also talking about the things floating around my head while on the road. Thus, scattered in the narrative of my trip, I will splice in topics that I found particularly relevant to my travels. Sometimes I searched out the topic, like when I downloaded a book about the National Parks before I left Boston, others presented themselves, like when I didn’t understand why I saw tons of wind turbines in Iowa, but few in neighboring ND, SD, and NB, even though those states sat on the best wind producing land in the country. I hope by talking about them you gain the context for why I was so excited to visit Yellowstone or see the oil rigs of West Texas and thus you enjoy the book more. Either way, these are not my original thoughts, more excerpts of books I listened to while on the road, combined with subsequent research and personal experiences. For this section, most of my information comes from Big Roads by Earl Swift, a remarkably engaging book given the topic.

In 1892 horses in New York City produced 6,000 gallons of urine and 2.5 million pounds of manure per day. With a horse for every six of the city’s residents, the city was drowning in an equine stench. Along with the cost of feeding and keeping the horses in good health, equal to the cost of maintaining the nation’s rail system, horses were begging to be replaced. Today there are only a few hundred horses left in the city. Long ago they were replaced by the motorized vehicle.

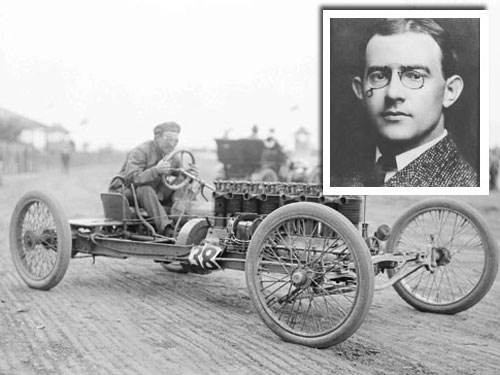

In America, the age of the automobile starts in many ways with Carl Fischer. Born in 1874, a sixth-grade dropout, prankster, and salesman, Fischer was transformed by his visit to America’s first auto show at Madison Square Garden. He returned to Indianapolis transfixed by mechanical buggies, sold his bicycle shop, and opened the Fisher Automobile company, the first auto dealership in the United States. To drum up sales he performed outlandish stunts: he dropped a Stoddard Dayton car from a sixth-floor downtown window and had it driven from the scene to show how sturdy it was; another time he attached a balloon to a Stoddard Dayton and flew out of town, promising to drive back from wherever he landed. Indianapolis loved it and Fisher became a local celebrity. The issue was that, no matter what he did on the sales front, American vehicles and the roads available to drive them on were woeful and far inferior to their European counterparts.

At the turn of the 20th century, the most common road improvement was to grade a dirt path in an attempt to smooth out its humps and bumps. A step up was a sand and clay mixture spread over an earthen bed which drained well and packed down hard with use. Above that was a gravel road that needed constant redressing due to constantly scattering pebbles. At the top of the pecking order was Macadam: a layer cake construction of crushed rock. Macadam consisted of a bottom level of large broken stones that were passed over with a heavy roller. Smaller broken stones were spread atop and pressed again by a heavy roller. Rock dust was then sprinkled on top of all that, watered down, and rolled a third time. Under the weight of the rollers, the rocks would stitch together forming a relatively smooth and stable surface. Yet in 1909, of the country’s 2.2 million miles of roads, only 8% had been improved in any way. During the rainy season, the unimproved dirt paths would become impassable and maroon farmers from markets for weeks at a time. The cars of the era were not much better, with hand-cranked starters, no tops, constant flat tires, and loud backfires.

Fisher’s solution was to build an auto racing track where the best cars and road materials of the day could be tested and improved. With his hometown of Indianapolis vying with Detroit as the auto capital of the nation, he figured it would be as good a place as any to build his track. Using the finest technique of the day, bituminous macadam, Fisher constructed a 2.6-mile track with perfectly banked corners. Driving legend and friend Barny Olefield remarked, “two miles per minute can be made with no greater danger [on the curve] than on the flat.” Unfortunately, the macadam construction, though sturdy at slow speeds, was not capable of remaining stitched together under the strain of solid rubber tires spinning at high speeds. On the first day of racing, just halfway through a 250-mile race Louis Chevrolet caught a rock through his goggles and had to be walked to the hospital. Then during the last race on the final day of the opening weekend, the front tire of the car driven by local boy Charles Merse exploded and his car went careening into the crowd, killing many. AAA threatened to boycott any future races if the track was not completely overhauled. The local coroner blamed the deaths on the inadequate track conditions. Fisher vowed a complete overhaul, and with the help of friend Arthur C. Newby repaved the entire track with 3.2 million 10 lb bricks. Thus the Brickyard was formed, and two years later in 1911 at the first Indy 500, 80,000 spectators were in attendance. The winner was Ray Harroun, who ditched his riding mechanic in favor of a rear-view mirror, the first time such a thing had been used in an automobile.

Fischer, as well-known and connected as anyone in the auto business at this point, next turned his attention to a transcontinental road. Cars were flying off lots as quickly as they could be produced. Vehicle registrations were on the brink of topping 1 million in 1912, having quadrupled in four years. People loved the sense of freedom the car offered and found vehicles far more sanitary than their equine counterparts. Much cheaper too, after factoring in the cost of maintaining a carriage’s drive train. Lacking were good roads to drive them on. Any ride into the country was an adventure requiring a four-foot plank, multiple spare tires, mechanical knowhow, and a tent if things went south. And that was when conditions were good. In the rainy season, dirt roads turned into mud, and transportation was put on hold. Fisher had little faith that government was up to the task. “The highways of America are built chiefly of politics, whereas the proper material is crushed rock or concrete.” He thought it was up to industry to lead the way and show what was possible. He envisioned a transcontinental highway spanning a dozen states from New York to California. Dry, smooth, safe, and not just passable, but comfortable in the rainy seasons. At a dinner in Indianapolis of 50 or so industry leaders, Fisher unveiled his plan. The highway would follow existing roads for much of its length, new construction connecting just those pieces which failed to connect, and then over time upgrades would modernize the highway to a uniform standard. Industry would provide the materials for the job, costing about $5000 per mile, and the public the muscle, with volunteers and local governments actually doing the labor. “Let’s build it before we are too old to enjoy it!” he implored his audience.

After lavish scouting trips, with western governors promising the moon and more to the passing highwaymen, the newly named Lincoln Highway was routed. Leaving New York it would follow a well-established route down to Philadelphia and across the midsections of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, to the outskirts of Chicago, before charting a new path through Cedar Rapids Iowa, Omaha Nebraska, and Cheyenne Wyoming, onto the old pony express trail through Salt Lake City, and all the way to San Francisco. On Halloween day 1913 the Lincoln was dedicated with fireworks, dances, and speeches in all the towns along the route. Over the next couple of years, these towns took pride in improving their sections of the highways. New Jersey remade its section in brick and concrete. In Illinois, thousands of adults and children voluntarily wielded picks and shovels trying to make their section the finest along the entire route. The improvements made a difference. Double the traffic passed through Ely Nevada in 1915 than the year earlier. Fish Springs Utah saw an uptick to 225 cars from 52 two years before. One driver even traveled its entire 3,389 mile length in 6 days, 10 hours, and 59 minutes.

Soon imitators were everywhere. The Jefferson Davis Highway from DC to SF by way of New Orleans; The Lakes to Gulf Highway from Duluth Minnesota to Galveston Texas; Ficher’s new project, the Dixie Highway from Chicago through Indy and Nashville, to his new development on a sandbar in Florida; and 250+ other named trails. More than 40 crossed Indiana and 64 were registered in Iowa alone. With each trail came a unique blaze design, tacked to trees, fences, and telephone poles, along its route. The Lincoln’s for example, was red, white, and blue, with a black capital L on the white stripe. The trouble was that the trails overlapped, a single stretch of road could be co-opted by a half-dozen trails, and the telephone poles could end up looking like a bunch of help wanted posters. Thus deciphering where one blaze ended and the next began, and which blaze you were supposed to follow, was a dangerous proposition, especially when many of the trails were more branding than an improved road. They were patchwork and inconsistent, but in total, they created our nation’s first interstate highway system. Further progress would have to wait until after The Great War.

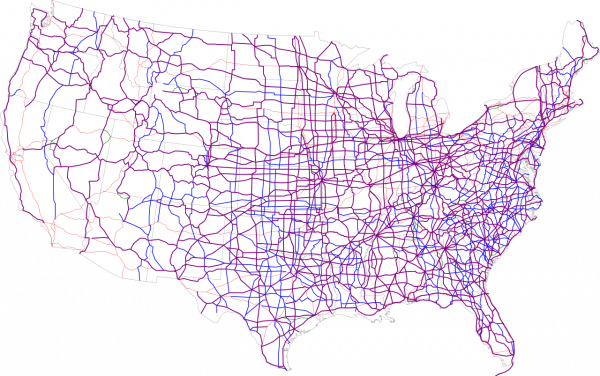

Part two of our highway story begins as Americans returned from the Great War victorious and took to the streets like never before. 1,396,892 cars were produced in 1919, the first year after the war; 1,731,435 cars two years after that. The cobweb of trail associations with their semi-improved roads wasn’t cutting it. The call for a national grid of federal highways grew deafening. With the speedy passage of the AASHO (The American Association of State Highway Officials) bill on Nov 9, 1921, they had their answer. States would remain the source of highways plans and the federal government the enforcer of design, construction, and maintenance standards. Each state was to designate a system of roads on which all federal aid was to be spent and which did not exceed 7% of the state’s total mileage. Additionally, each road within the system was to be labeled as either a primary or secondary road. The former being of an interstate nature; the latter connecting farms to market, small towns to one another, and other strictly local destinations. With its passage, the single most important ingredient of our modern road system came into being.

At the head of its implementation stood Thomas Macdonald, an Iowan curmudgeon, who as a kid required his younger siblings to call him sir, and would go on to serve as highway chief for six consecutive presidents. Called chief by everyone, including his wife, he was a meticulous engineer who had the respect and trust of everyone in Washington. Facts, figures, and research were the backbone of the department’s decisions under his leadership. Thus after the department sent maps to the 48 states asking for their primary and secondary road candidates, he asked a trusted young engineer Edwin W. James to lead a committee to come up with an internal model of where they thought roads should go, so the department could better judge the quality of the state’s choices. For this task, James collected the population totals for each county from the previous census, plus four economic indicators: agricultural production, manufacturing output, mineral yield, and income from forest products. Then he calculated the percentage contribution each county made to the state’s total population. He repeated the exercise for the four economic indicators. Averaging the numbers gave a quick and dirty gauge for a county’s relative importance. James then shaded in each county, darker for increased importance within the state. Once finished the committee had a map with best to worst routing possibilities staring them in the face. Good routes would be darkly shaded and go through the more economically productive counties. It would also be easy to see that a state's choice was clearly erroneous if it went through lightly shaded counties. The state’s nominations started rolling in and for the most part adhered to the federal model. In total the proposed roads would stretch 168,881 miles and reach 90% of the nation’s population, with not one or two transcontinental routes but dozens.

Next up was the naming of the new roads. At a joint meeting of state and local highwaymen led by Macdonald, four pillars of road design were hammered out. First, it was quickly agreed to number the nation's roads rather than naming them and to choose the routes to be included before applying the numbering. Second, Frank Rodgers of Michigan doodled a shield, like the one that adorns the $1 bill, and passed it to Edwin W. James, who added a small US over a large route number and the name of the state above the shield’s crown. The design was approved on the spot as the marker that would identify all the routes included on the numbered system. Third, the men formally adopted the red, yellow, green, stoplight sequence, and the octagonal stop sign, painted black on yellow at the time because a durable red paint was not available until the mid-50s. The actual numbering of the system was delegated to a committee chaired by James to decide. AB Fletcher, a former California highway chief, came to James proposing the grandest highway of them all, stretching from the top of Maine down to the southern tip of Florida in Key West, with the fitting name of highway 1. Thinking about it James wondered where 2, 5, 10, and 50 would be laid. A pattern suggested itself, “It stares one in the face, it is so simple and adjustable.” He would assign even numbers to all the east-west highways and odd numbers to all those running north-south. The numbering would be lowest in both directions in the northeast corner of the country at Maine’s border with Canada and would climb as one moved south and west. One or two-digit numbers would denote principal highways, with three-digit numbers signaling a spur or variant of a main route. To bring more order, the major transcontinental routes going east-west would have numbers ending in 0 and the most important north-south highways would have numbers ending in 1. Thus with Route 2 running east-west in the northernmost climbs and Route 98 running deep in the south, route 50 was almost guaranteed to run like a belt across the country’s middle. Likewise, the intersection of routes 21 and 60 would indicate you were towards the east and just a little south of center. Unfortunately, when the agriculture secretary signed off on the plan, there were scores of complaints from trail associations about their assigned numbering or lack of inclusion and from states about their lack of major routes. The most serious complaint came from Kentucky Governor William J. Fields, who pointed out that route 60 did not run from the east coast to the west as one might predict, but from Chicago on a long arching route through St. Louis, Tulsa, and Albuquerque to Los Angeles. US 50 missed Kentucky to the north and US 70 missed it to the south, so US 60 in theory should go through his very important state. With a contingent of his state’s congressmen, Fields took his case to the chief. Macdonald was won over by Fields’ use of logic to point out the flaws in the map. The route from Newport News VA to Springfield MO, running through Kentucky would now be named US 60 and the Chicago to LA route renamed route 66. Thus the historic Route 66 was born! That was not the only anomaly in the numbering though. Highways braided, sometimes in their proper sequence, but other times not at all. US 11 for instance curved so much at its southern end that it ended west of route 49. The Lincoln, the nation’s first mother road, became route 30 from Pennsylvania to Wyoming, before turning into a half dozen other numbers towards its end.

The very next year after the AASHO bill’s passage, 10,000+ miles of federal-aid highways were built, with Motor Life Magazine saying of Macdonald, “At his nod, millions move from the US Treasury. Neither Morgan, nor Rockefeller, nor Carnegie, ever had the spending of so much money in so short a period of time.” Meanwhile, the automobile industry continued to boom. In 1922 Essex developed the first enclosed car, sealed off from the elements, making motoring a year-round possibility. In 1923 American factories produced 3.9 million cars and trucks with registrations topping 15 million. With all these new highways and new drivers, businesses started appearing on the roadside catering to the motorist. Lodging began simply with towns offering public campgrounds equipped with a tent site, fire ring, trash can, and parking spot. For-profit campgrounds then sprang up boosting offerings such as little cabins for those not inclined to tents. The idea took hold and roadside cabin camps were available coast to coast. Some went as far as offering Simmens or BeautyRest beds and dropping cabin from their name in favor of motor court or motel.

These new roads were not just a new toy for the weekend joy ride though, they were fundamentally changing the appearance of their surroundings. When personal speed had topped out at a horse's trot, cities tended to be compact and mostly circular in shape. The invention of commuter rail allowed workers to live along the rail lines; resulting in development like the spokes of a wheel as the train lines radiated out from the city center. The advent of the car filled in the in-between places and then began to grow outwards.

It did not take long for the new US highways, built right through the center of towns, to start clogging up with the incredible influx of new vehicles. As they did, the bypass movement began. The theory went that by building a route around the city much of the traffic would be diverted around the clogged core. Unfortunately, it would be discovered that most of traffic was intra-city with a very small contribution being made by through travelers. Journeys of less than 30 miles accounted for 88% of all trips, and those of greater than 500 miles accounted for <.1%. The bypass failed in another way as well. With cities sprawling outward a new bypass would in 5 years be gobbled up by the city. Businesses would sprout up on its edges and a new bypass would need to be built even farther out.

By the 1940s people came to see that the US highway system, and subsequent bypasses, were not the solution to all their congestion troubles. As Benton Mackay, the father of the Appalachian Trail, said of the US highways, “the flanks are crowded with food stands, souvenir shops, and billboards, each an eyesore, and parking lots and driveways a potential hazard….A break from America’s equine past required a highway completely free from horses, carriages, pedestrians, towns, and grade crossings. A highway built for the motorist and kept free from encroachment except for the filling stations and restaurants needed for his convenience.” He was asking for a grade-separated, limited access highway with all the fluff removed from its sides.

Little did Mackey know but a plan for such a system was already underway. In 1938 Macdonald got called to a meeting with FDR in the White House where the president drew six blue lines, three vertically from north to south, and three horizontally from coast to coast. He was intrigued by the idea of building such roads and asked the chief to look into the matter and report back.

A few weeks later Macdonald received a similar request from Congress to report on the feasibility of such transcontinental routes. Titled, Toll Roads and Free Roads, the report was split into two parts, on the feasibility of transcontinental toll roads, and an alternative conceived of by the bureau. In summary, it said that the six transcontinental routes were buildable sure enough, but that they would not address the country's true highway needs, nor recover their costs in tolls. The cost of such a system would be $184 million per year through 1960, but by the most optimistic estimate, they would recover only $72.4 million in tolls each year. Even the NJ to CT section, the busiest in the system, would fail to break even. Plus coast to coast traffic amounted to only 300 cars per day. Only 800 cars traveled to the west coast from any location east of the Mississippi. Such demand did not justify a huge public outlay. Macdonald thought that an overbuilt road was every bit as shameful as a deficient one. Unless it was justified economically, it failed, regardless of its engineering.

Part two of the report, the alternative, suggested a 26,700-mile system of free highways. It turned out to be the blueprint for the modern interstate highway system. Its mileage would be twice that of FDR’s six transcontinental routes with most of its legs, not superhighways but two-laners, no more and no less than their usage demanded. The second part of the report also went out of its way to emphasize the need for urban highways. Congestion wasn’t caused by thru-traffic mixing with local, it was caused by a multitude of small movements by locals. For example, of the 20,500 vehicles entering DC each day, only 2,269 or 11% were by-passable. The answer wasn’t to bend a highway around a city but to drill it right through its middle. As for tolls, they had no place on these or any road. Roads were a birthright akin to public schooling. Plus tolls saddled engineers with a no-win situation; to attract users the toll road had to offer a better product than parallel free roads, which limited the possible improvements to those free roads no matter how badly needed they were. Alternatively, improve the free roads too much and your toll road would lose too many customers and require state subsidy.

Looking past the war, FDR saw the need for re-incorporating millions of fighting men back into the labor market and retooling the country’s high revving war industries once the fighting stopped. Thus in 1943, he sent an updated draft of the report to Congress, urging prompt action to facilitate the acquisition of land, the drawing of plans, and the preliminary work which must precede actual construction. It received a warm reception on the hill and in 1944 Congress incorporated the proposal into the annual highway bill with little fanfare. It went “There shall be designed within the continental United States a national system of interstate highways, and which specified such a system should not top 40,000 miles in length and should be so located to connect by routes direct as practicable the principal metropolitan areas, cities, and industrial centers to serve the national defense and to connect at suitable border points with routes of continental importance in the Dominion of Canada and the Republic of Mexico.” The bill also specified a quarter of each year’s appropriation could go towards building urban highways. Unfortunately, the bill provided no special financing for the system or a timeline of when construction would begin. Yet it was still a major step. It committed the interstates to paper, now all that was needed was to find the money to build them.

Years passed and the need for the new Interstates only grew. Population numbers exploded. New Orleans doubled in size in the ’40s. SF multiplied 2.5 times its pre-war size. And more cars than ever were getting pumped onto the nation’s roads. In 1949 three fourths of all the cars on the planet were located in the US. New York alone thought it would cost $1 billion to restore its roads to the efficiency they enjoyed in 1930.

The theory goes that Dwight D. Eisenhower was inspired to build the Interstate system by two trips he took earlier in his career which showed him the necessity of good roads. The first was in 1919, when as a young officer he took part in a military caravan to the west coast along the Lincoln Highway that was felled by every type of misfortune a road trip back then was liable to, due to the inconsistency of road conditions. The second was advancing across the impeccably built German autobahns on the Allies’ march to Berlin. Wrong. The interstates were a done deal in every major aspect except for financing by the time he entered politics. On the day when FDR called the Chief to his office and drew those six blue lines, Eisenhower was serving in the Philippines as chief of staff to Douglas Macarthur. When FDR submitted the highway report to Congress Ike was just taking command of allied forces in Europe. When the system received its first paltry $25 million allocation Ike was the head of the West’s cold war alliance. In fact, by the time Ike took office in 1953, the system had been in existence for 8 years. Nevertheless, as I drove on I-90 west out of Buffalo with the sparkling water of the Erie on my right, it was Eisenhower’s name on the little blue sign which adorned the shoulder of the road. That is because, with some encouragement from Ike, Congress passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, funding the system Macdonald and Fairbank had put on paper 18 years earlier. The bill stipulated 90% federal financing of a 40,000-mile Interstate system, to be built over the next 13 years. The money would come from new taxes on tires and gasoline, which would be put into a new Highway Trust Fund to be used only for highways.

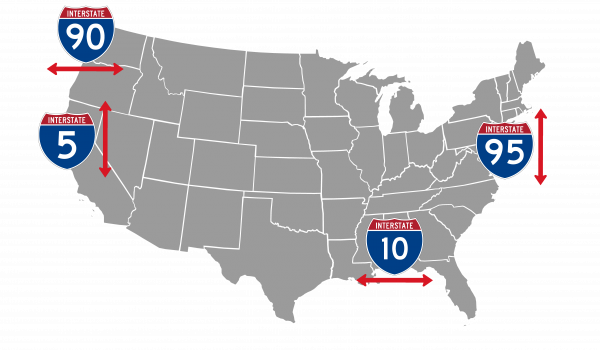

The bureau, with a new head engineer Frank Turner, a soft-spoken bus-riding Macdonald protege who had proven himself on the Alaska Highway and by helping rebuild the Philippines after WWII, had been busy in the intervening years testing the best materials and designs for the new system. For signage they hired a corps of engineers to drive around a parking lot at night peering at signs containing six words, balk, farm, navy, stop, zone, and duck, in different combinations of typeface and spacing. Green, blue, and black signs were also tried. Nearly 6 in 10 favored a green background, up and down lettering was preferred to all caps, and as spacing between letters increased so did the distance at which people could read them. To determine the proper road material, six test loops were built of varying paving material and thickness, 836 sections in all, on which army transport soldiers would drive 126 trucks around in circles for 19 hours per day for 2 years. By the end, the soldiers had racked up 17 million miles. The conclusion, the thicker the pavement and subgrade, the better. Since the numbering system of the US Highways had worked so well, it was recycled with a few minor alterations to the new Interstate system. To avoid confusion of overlapping numbers between the two systems it was proposed that no state would have an Interstate and US highway with the same number within its borders. To accommodate this, the Interstates would be lowest in the south and west and highest at Maine’s border with Canada. Plus, they would ditch naming roads I-50 and I-60 to avoid overlap across the country’s middle. Additionally, the major north-south routes would now end in 5 instead of 1. So if you were at the intersection of I-10 and I-5, it meant you were in the south-westernmost part of the states. It also meant that for a road like I-90, which most Bostonians think starts at their city’s airport, actually starts all the way west in Seattle, and terminates at Logan.

Designed, tested, and now finally financed, the largest public works project in history was underway. Billions started to flow from the government’s purse strings, each billion creating 48,000 full-time jobs for a year, consuming 16 barrels of cement, 1 billion pounds of steel, 18 million pounds of explosives, 123 million gallons of petroleum products, 152 billion pounds of aggregate, and enough earth to bury NJ knee-deep.

By 1962 about 12,500 miles or 30% of the system was open to traffic and another 34 miles were opening every week. They were fast, safe, and Americans fell in love with them. They loved the act itself, the feeling of the engine under their control. Americans did not have an automotive life foisted upon them. They did not buy homes far from work or forsake mass transit or pave over their cities because they were manipulated into doing so. They wanted roads, they wanted the Interstates, and they wanted them pronto.

Just as with the US Highways, the changes brought by the new roads affected life far off from its paved borders. Small towns bypassed by the interstates found their livelihoods vanish. A gas station on US 80 lost 80% of its customers when I-20 was built. A motel on historic Route 66 in Qualpo Oklahoma bought a few years before for $28,000 went on the market for $5,000 and found no takers. Manufacturing departed cities for cheap, abundant land near the Interstates, which provided them with a ready distribution network. Chrysler credited the proximity of I-90 for building an $850 billion factory in tiny Belvadere Illinois and I-44 for its construction of an assembly plant in the Ozarks of Missouri. Led by jobs and the desire for a house and a yard, the suburbs boomed. No longer able to locate themselves on the road’s shoulder, housing and shopping developments migrated to exits and radiated out from there; nucleated development it would come to be called. With people and manufacturing jobs leaving, the central business districts of cities began to fall apart. Mass transit withered in the new environment, with low-density developments out in the suburbs and jobs spread out all over the place, there were not enough common destinations to make fixed rail lines viable. The only form of transportation suited to this new urban sprawl was the very agent of its change, the car. Thus, in a sick twist of logic, highwaymen believed that only more and bigger highways could entice suburbanites to make the trek back into the city center and thus avoid a complete abandonment of downtown.

The experience of driving changed as well. Everything sped up. Restaurants began popping up at exits catering to road warriors in a hurry. They used shorthands, a logo, a color, or a certain shape of the roof to signal their presence. They aimed to provide the driver with a predictable experience, such that a traveler might ask themselves, “should I search out a hit or miss local spot that could cost me an hour or should I grab a decent Mcdonalds burger at a great price and be back on my way in 10 minutes flat?” The latter option often won out, which is why today the look and feel of Interstate exits with their identical chain restaurants have more in common with one another than they do with the state or locale they are in.

Not everybody was overjoyed with these changes. SF had a vision of connecting the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge with a looping freeway along the peninsula's watery edge. What they got was a 57ft tall double-decker expressway passing right in front of the Ferry Building and blocking the city’s residents from their historic waterway. The uproar of displeasure was so intense that on Jan 27, 1959, the Board of Supervisors approved a resolution opposing 7 of the 10 freeways planned for the city. Louis Mumford, the visionary social critique, found his way into the hearts of urban planners everywhere with his scathing critiques of the Interstates. “The experts have innocent notions that the problem can be solved by increasing the capacity of the existing traffic routes, or multiplying the number of ways getting in and out of town, or providing more parking spaces for cars. Roads in NYC were designed for a city of four-story buildings. Now in effect, we have piled three NYCs on top of one another. The roadway and sidewalks flanking them should, if they are kept at the original ratio, be 200 ft wide, the current width of a NYC block.” He went on, “Want to save the cities? Forget about the motor car, the solution laid in restoring a human scale to urban life, in making it possible for the pedestrian to exist. A choice was looming, for either the motor car will drive us all out of the cities, or the cities will have to drive out the motor car.” The most surprising critic of the new urban highways, though, was the man who spurred their financing. In 1959, on a drive outside Washington to Camp David, Ike’s limo bogged down in traffic due to the construction of a new Interstate. Riled, Ike demanded an explanation, for this was far too close to Washington to comply with Eisenhower’s notion of a largely rural intercity Interstate system. An examination of congressional intent ensued, but it concluded that every study on which the program had been based was explicit, the country’s highway needs were sharpest in the cities; Congress had read those studies, Congress had seen the proposed routes drawn out on a map, Congress had wanted urban routes. Eisenhower's displeasure with his own system would have to remain just that.

The collective acrimony over the damage of urban Interstates pushed Congress in 1968 to require two hearings on federal-aid highways. The first, a corridor hearing, at which taxpayers could speak their minds on a highway’s location. The second, a design hearing, at which they would have the opportunity to affect the project’s size and style. In addition, from then on, anyone unhappy with a state highway commission’s decision could appeal the matter directly to the feds on any one of 21 grounds: these included, the state had failed to weigh neighborhood character, property values, natural or historic landmarks, conservation, or the displacement of households or businesses. The grounds for appeal were so commonplace that every remaining interstate project was almost sure to be challenged, and left in a perpetual state of appeals.

This marked the beginning of the end for highway building in America. Some of the more difficult portions of the interstate system dragged on for years, but for the most part, the roads then are the roads now. The highway program had been bigger than the space program or atomic energy and had delivered on much of its promise. 70mph on the flat was attainable year around, and the fatality rate on American roads was just 2.52 per million miles driven, down from 16 per million miles driven in 1929. The cost to uproot people and pave over livelihoods became too high to build anymore though. As time went by, those cities, where the need for highways had been greatest, began calling for public transportation. People saw how the car had gutted many downtowns, leaving them ghostly quiet in the post-work darkness. Instead, they wanted a return of the tangled, creative, feverish energy only a pedestrian-focused metropolis could provide.

In 1982 they were successful in splitting the Highway Trust Fund in two with the new part designated for mass transit. Congress also authorized states to scrap existing federal aid highway plans and transfer the money to a mass transit project if they wanted to; thus states would no longer have to turn down federal aid if they did not want to build yet another highway.

Highwaymen, for their part, could not understand why they were becoming so maligned. Sure a few urban routes necessitated serious upheaval, but as a whole, the interstate system had been built quickly, efficiently, and provided a massive boon to the communities it passed through. Turner viewed highways as windfalls if you counted the amount of time they saved the taxpayer, the lives they spared, and the goods they carried. They were the only government activity that repaid the taxpayer with interest, and they more than compensated for whatever damage they caused.